Originally published in The Globe and Mail (June 7, 2018).

“The only safe thing is to take a chance.” That was Elaine May’s motto, according to her one-time comedic partner Mike Nichols, and it served the trail-blazing comedian, actress, screenwriter and director well. For a while. In 1987, her comedy Ishtar became one of the worst-received financial flops in Hollywood history, and tragically ended May’s short run as a director.

This month, May is receiving the retrospective treatment at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in a series titled Funny Girl: The Films of Elaine May, running June 8 to 30. Local film programmer Alicia Fletcher’s curation of all four of May’s directorial efforts, plus a handful of the films she wrote, is a well-researched commemoration of the formidable talent. Ideally, it will not only introduce a new generation of cinephiles to May’s work, but also re-examine and legitimize May’s troubled and storied career and invite more efforts to rewrite the film canon from the perspective of the female creative.

In the 1970s, May was granted artistic freedom at a time when exceptionally few women were allowed to direct studio films. Before May, only two women – Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino – had directed movies in Hollywood since the pre-1930s silent era.

May made four films – only four. A New Leaf (1971) is a black romantic comedy satirizing lavish lifestyles, starring Walter Matthau and May herself. The Neil Simon-scripted The Heartbreak Kid was released the following year, another rom-com that acerbically skewers Jewish identity. In 1976, May directed Peter Falk and John Cassavetes in Mikey and Nicky, a tragic take on the male-buddy comedy that nearly tripled its US$1.6-million budget.

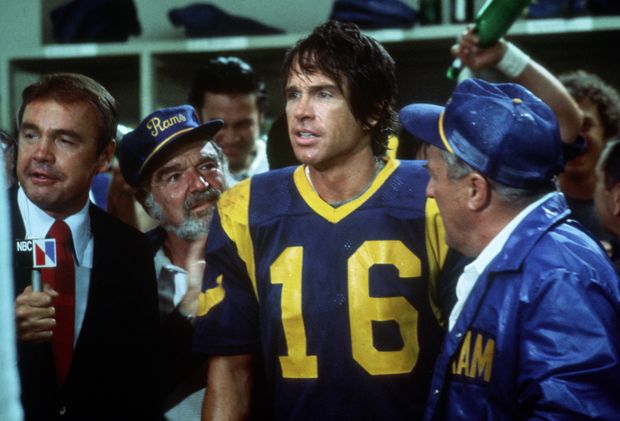

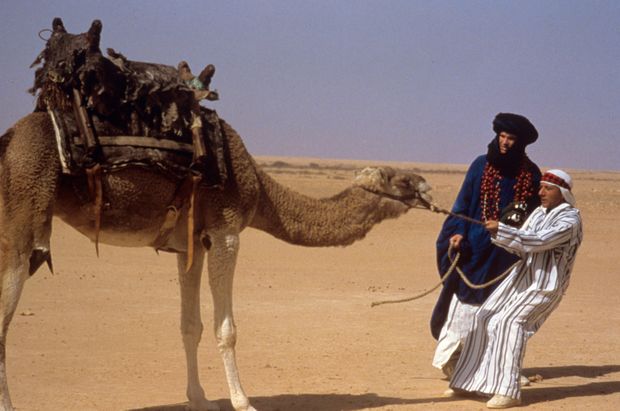

May didn’t direct for another decade, until Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman – for whom she had previously written or co-written screenplays (Heaven Can Wait, Reds and Tootsie) – revived her career using their clout and privilege. Yet the trio’s project, Ishtar, was a financial and critical disaster. Some have argued its unflattering portrayal of ignorant Westerners in the Middle East may have sunk it, but multiple media reports about its troubled production didn’t help, either. The movie quickly became a metonymy for Hollywood financial disasters caused by excess or creative perfectionism.

With her directing career permanently over, May returned to acting (In the Spirit, Small Time Crooks) and writing screenplays, sometimes uncredited (The Birdcage, Primary Colors, Dangerous Minds and others). Most recently, she’s tied to an upcoming Broadway production by Kenneth Lonergan, co-starring Michael Cera.

Much has been made of May’s perfectionism; it’s a trait we admire in auteurs like Stanley Kubrick, but May’s legacy – or lack thereof – suggests that we haven’t reached a point where we tolerate it from women artists.

On the set of Mikey and Nicky, May was known to keep the camera rolling to capture Falk and Cassavetes in a more candid state, and in one case the film kept rolling for hours after the actors had left the set. She shot an imprudent 1.4 million feet of film, resulting in power struggles between studio Paramount and the director, who stole the finished print as leverage to have final cut on her film.

She was equally spendthrift on Ishtar, doing 50 takes of a scene involving vultures and requesting an extensive and eventually abandoned search for sand dunes in the Sahara Desert. The poor management of the production – only partially her fault, as fights and drama broke out between all players on set – delegitimized her reputation for control over a studio production.

When May directed her own screenplays, she was equally uncompromising. Her original script for A New Leaf, starring Matthau as a once-wealthy socialite intent on marrying then murdering a woman for her wealth, involved killing off two other characters. When Paramount cut these scenes from May’s final version, she no longer wanted to be associated with the project (one wonders if a director’s cut will ever be found).

Creative perfectionism has a double standard in Hollywood; where male auteurs like Alfred Hitchcock and Kubrick – who worked inside or outside of the studio system – are revered for their artistic rigour, May’s stubbornness only tarnished her reputation as a capable, serious filmmaker.

This is a shame, as motifs across May’s work suggest auteurism and the work of a visionary. Consider her adept use of props and costumes, like the ridiculous headbands and outfits in Ishtar, or the sudden, flamboyant introduction of an electric pepper mill in A New Leaf. Her use of repetitive dialogue as a gag is existential – the “40 to 50 years” line in The Heartbreak Kid, for example, is haunting enough to turn anyone off long-term relationships. Her visual storytelling was recognizable and fully realized from her very first film, a unique satire that made romance painful to watch.

Given May’s well-known battles with the studios, it’s no surprise her public presence oscillated between a love for the spotlight and an aversion to publicity (the last in-depth interview she did was in 2013 for Vanity Fair). Her reluctance to protest her fate as a director is perhaps an act more telling of the industry that washed her out than of May herself. Yet the short, bitter end to her directing career is tragic, given her tremendous talent; equally lamentable is the sheer inaccessibility of her work. Of her four films, only the worst and best are available on Blu-ray and iTunes: Ishtar’s Blu-ray has no special features, but Olive Films’ beautiful transfer of A New Leaf comes with a smorgasbord of keenly researched supplements that gives May her due.

In hindsight, reading about May’s career can provoke anger toward the entertainment hegemony that belittled her. The public discourse of #MeToo and contemporary feminism has empowered women in the most competitive industry in the world to speak out about the difficulty of being taken seriously in Hollywood in any role, and in directing most of all. When a woman is given a chance to direct, like May was 49 years ago, the odds seem stacked against her efforts to establish a creative vision without undue scrutiny, and with the same confidence, patience and opportunities granted to male directors.

Not much has changed: Last year, women made up only eight per cent of directors of the 100 top-grossing films. The number of total Hollywood directors in May’s time was 0.9 per cent between 1949 and 1979.

Despite May being that rare woman in the industry, the content of her films has been criticized by feminists, particularly her unmistakable sympathy toward male protagonists, who dominate her narratives. Her unsettling ambivalence toward female characters – more a cruel, frank portrayal of how men see women as unlikeable, unflattering or weak – would likely make today’s audiences uncomfortable, given our desire to see more films and series with female perspectives that endear us to their plights.

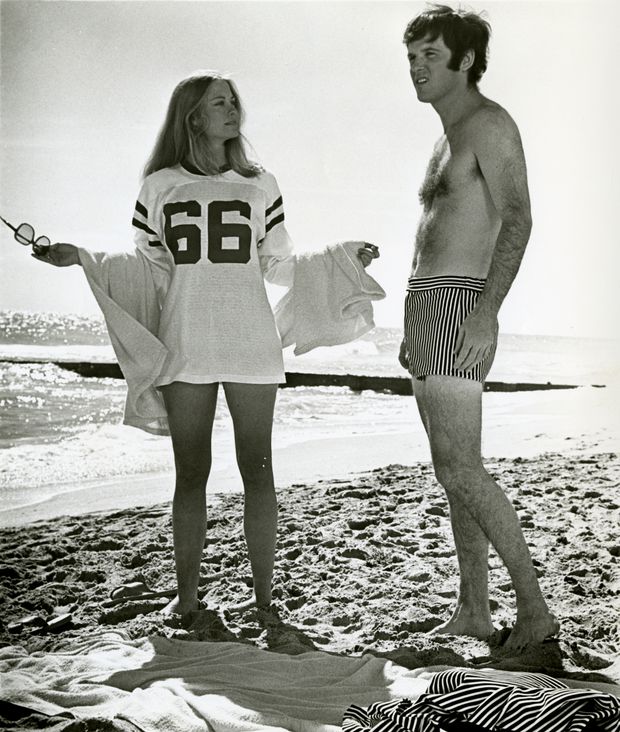

Yet film scholar Barbara Quart suggests that May’s focus on male-centric stories may have been a way to appease studios reluctant to let a woman direct. Another reading is to see her sharp comedy, which enables us to understand male characters’ appalling selfishness and feeble-mindedness, as a deeply cynical perspective on human nature. In A New Leaf, Matthau’s Henry wants to kill his wife, Henrietta. In The Heartbreak Kid, Charles Grodin’s Leonard ditches his new bride on their honeymoon for a gentile blonde. These comedies are more agonizing than their dramatic premises and suggest that compared to drama, comedy is closer to real life.

Arguably, May is the most gifted when she’s onscreen herself, as the unforgettable, unwieldy, scatterbrained botanist Henrietta in A New Leaf. If she’d been given a fraction of the time and opportunity to finesse her craft as a director as she had as a comedian, who knows what kind of films she could have created?

“If you can’t be immortal, why bother?” asks Henry in A New Leaf, a film that challenges gendered notions of authorship, notably when the naive Henrietta romantically chooses to name the species of plant she has found after her contemptuous husband instead of herself.

Today, we can help Elaine May “achieve a small slice of immortality,” as Henry puts it. Instead of associating her name with the notoriety of Ishtar, let’s reconsider her small, but rich and underappreciated body of work.

Funny Girl: The Films of Elaine May runs through June 30 at the TIFF Bell Lightbox (tiff.net)