Several days ago I overheard some folks on an elevator describing their experiences rushing tickets at TIFF. Your best bet with rush is to stand in the much shorter lines for the lesser-known or more experimental fare. One woman described how she’s attended several “weird” films at the festival and found herself invariably sleeping through almost all of them. But she didn’t mind: “I sometimes dreamt about the movie I was watching.” It’s an experience I think we’ve all had at some point or another, particularly the underslept festival goers bouncing from one four-film day to the next.

From the description, the woman in the elevator had probably unwittingly attended TIFF’s experimental programme Wavelengths, which is notable in consistently selecting some of the most interesting and daring films in the world. It offers a unique component to TIFF’s often bloated programming (which has been cut down 20% yet still sometimes feels like more noise than signal). Wavelengths is a contrast to the red-carpet glitz and glamour, especially for cinephiles who don’t care as much for mainstream movies or don’t want to waste their time at a festival when such movies are opening theatrically in a matter of days, weeks or months. The program also offers a rare opportunity to watch experimental films in their intended projection. It can also be a boon for Canadian filmmakers.

One of its selections this year comes from Canadian filmmaker Denis Cote, who has marked out a rich body of work alternating between meditative, quiet documentaries (“Bestiaire”) and low-key dramas that depict Quebecois society (“Vic + Flo Saw A Bear”). This year he’s back with something in the former category: “Ta peau si lisse,” or “Skin So Soft,” a reflective look at 12 bodybuilders as they go about their daily routines. It takes a lot of time to perfect their physical physiques: Constantly downing protein, flexing muscles, practicing poses, and in a few of the men, training others. The film’s editing rigor reveals a rich variety of training methods, self-care routines, dietary and lifestyle choices, and how these men manage to fit training into their family lives.

The film suggests that, as much as it is a documentary exploring a particular subculture, the hypermasculine ideals that bodybuilding espouses and turns material in the bulking muscles of its practitioners do form from some degree of emotional vulnerability, a history of inferiority, the person needing to compete against someone or something. These are the subtle vibes I picked up while watching one of the bodybuilders listen to a music video through headphones on his laptop as he shovelled food into his mouth, almost angrily. It’s not so much anger, I realized, watching him watching his laptop so intently, as anxiety. And then a tear rolls down his face. There’s a lot going on here. The act of fuelling himself a high-protein, healthy-fat meal (smears of avocado forgotten on his mouth) while watching something so emotionally intense for him is a form of restoration, yet there is something inherently defensive about such acts, about such cold determination.

But Cote is not here to judge, simply observe, and that empathy continues through to the film’s end, when the men do finally engage in a more casual form of restoration: They bus to a cottage to relax and unwind, helping each other with their poses, swimming in the lake, basking in the sun, and taking some much needed rest after a trying tournament. Even bodybuilders need to recharge their batteries, and “Skin So Soft,” in revealing some of the vulnerabilities of its subjects, demonstrates the multifaceted lives these men live.

The short preceding Cote’s film is Torontonian Kazik Radwanski’s “Scaffold,” a quietly humorous look at the exchanges between two male immigrant contractors (likely Eastern European) working on a house in a Toronto suburb. We never see their faces, only hands and offscreen voices, as they renovate a backyard door and a second-story window. Their exchanges with the bourgeois house-owner are hilarious, even Bunuelian, in their trivial absurdity. Through the window, she offers one of the men coffee in fancy floral china cups, which go from being firmly to precariously held as he graciously accepts her good will while balancing on the scaffolding. He then wisely suggests to transfer the liquid contents to his rugged thermos, lest he break her delicate china.

That professional fear of breaking the client’s refined things is presented in other funny scenarios across the film. Repeated shots of the men’s hands as they glob on paint and grab and recharge power tools help paint a picture of the large, sometimes unrestrained gestures and physical actions required of the job and how such a gruff masculine identity shores up against the delicate and refined upper-middle-class of the house within that we, along with the men, don’t get to see much of. Radwanski isn’t going after any obvious class division here, but his restrained and authentic approach to showing a small, simple glimpse into the laborers’ lives does all the work for him.

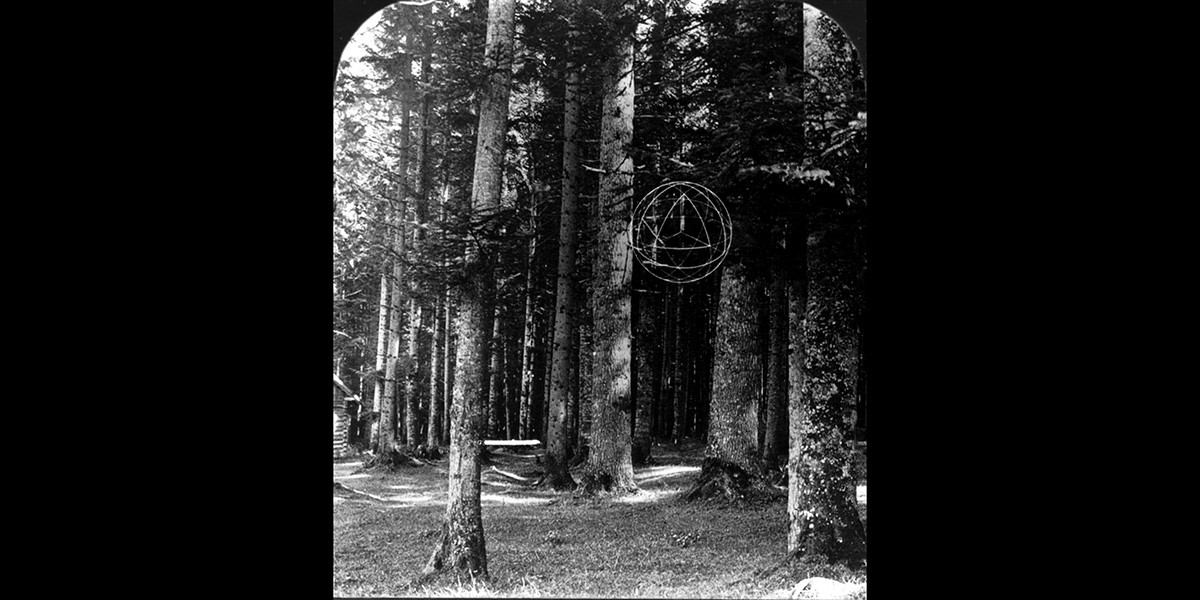

Moving from the simple to the complex, we have “Prototype,” the feature debut from Toronto-based experimental short filmmaker Blake Williams. This is the kind of film you need to see more than once in order to begin to truly absorb this profound and complex work. The film begins with stereoscopic images showing the ruins after the Galveston hurricane of 1900, before moving onto more abstract and arresting forms of 3D imagery that occasionally feel experiential—claustrophobic, lonely, often both—and occasionally more textual types of imagery that ground Williams’ examination of his historical preoccupations. The results are shocking and somewhat overwhelming (thus the need for a rewatch). Using vintage Philco screens to re-photograph and reprocess his own material, Williams gives the viewer a heady mix of ideas that at times might feel a little overwhelming in their transitions, yet it’s exactly the kind of film that you can still easily sit back and let wash over you.

Originally published on RogerEbert.com (Sept. 13, 2017).