Here is a trio of documentaries that, as different as they are, all pertain to the power of friendships and relationships, professional and personal, for better or for worse. Falling in the “worse” category are Argentine tango legends Juan Carlos Copes and María Nieves Rego in German Kral’s “Our Last Tango,” which was produced by Wim Wenders. Despite a rocky relationship, the two continued to dance together for years because of their undeniable chemistry on the dance floor, making tango a worldwide sensation with their “Tango Argentino” Broadway show in the 1980s. Now octogenarians, the dancers are interviewed separately, implying that they are not on good enough terms to talk to each other. Likely unintentionally, the film pits the dancers against each other, putting the viewer in the awkward position of having to decide which one to sympathize with.

Though the heart of the film is about Copes and Nieves’ tumultuous time together, “Our Last Tango” also chronicles the importance of tango in their home country, starting with the duo’s humble beginnings as non-professionals and the various trials and tribulations they encountered in keeping the dance relevant in the decades to follow. Using performance footage and warm-hued, soft-lensed dramatizations of their younger days, the film is successful in portraying the competitive career of dance. But in focusing so much on their present-day bitterness and regrets, “Our Last Tango” loses a key opportunity to engage audiences who don’t know much about tango with the more intricate details of what it’s all about, and why it matters. You could argue that perhaps that’s not the purpose of this documentary, but at the same time, you’d think the world’s most beloved experts would have a thing or two to say on the subject. Instead, we get such an intimate glimpse into their personal lives that the film loses momentum and becomes a kind of soap-opera-through-flashback. “Our Last Tango” proves that old adage, “It takes two to tango,” is quite true, but with one caveat: Choose your partner wisely.

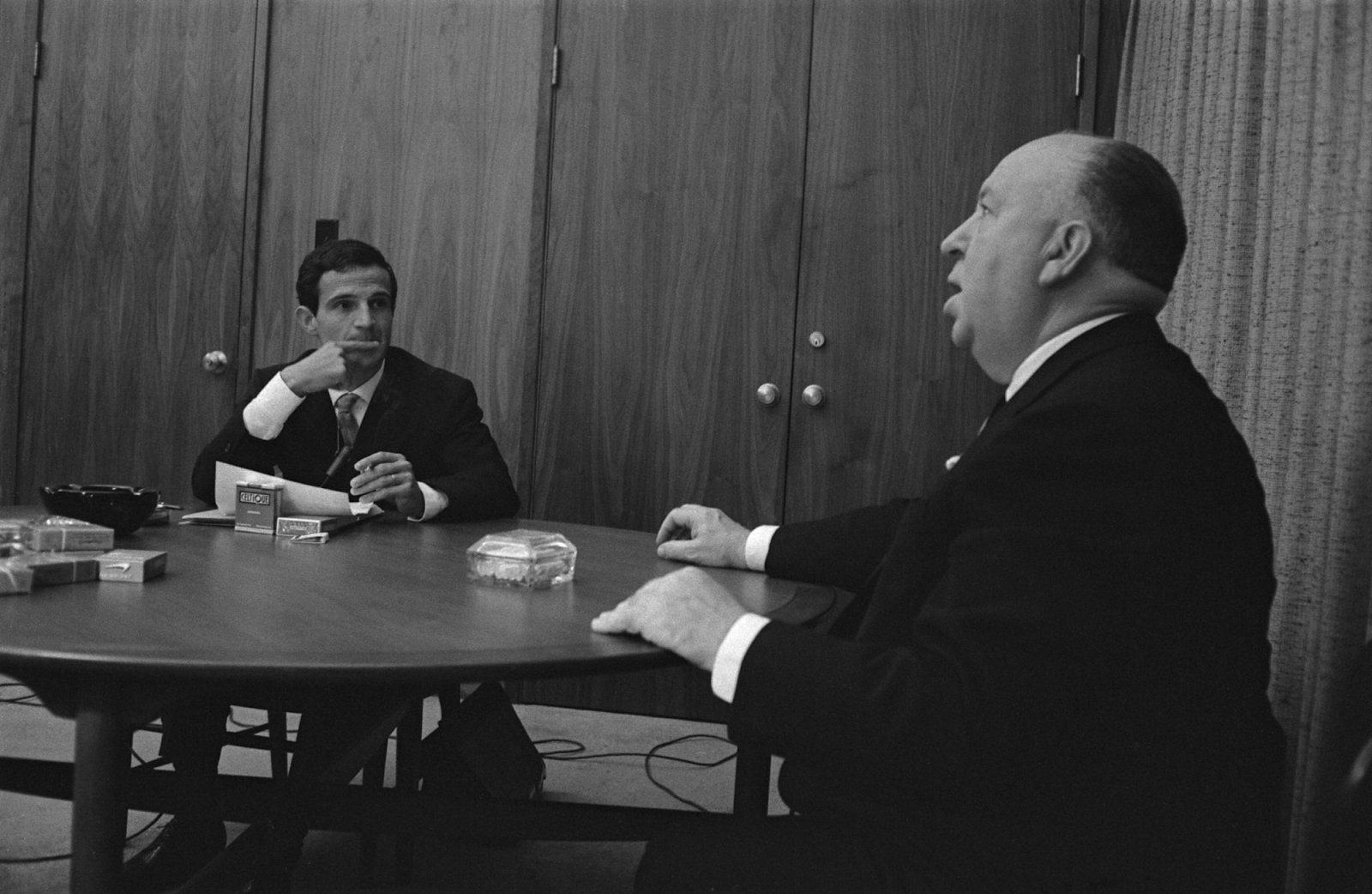

While “Our Last Tango” dwells too much on the personal, Kent Jones’ “Hitchcock/Truffaut” doesn’t do it enough. An in-depth tribute to the famous book that can be found in every cinephile’s library, the film uses Francois Truffaut’s long-form interview with Alfred Hitchcock as a jumping-off point to delve into the myriad aesthetic considerations of the British auteur’s large body of work. Here, we get a tiny glimpse into the interior world of Hitchcock—the word “perversion” is mentioned a small handful of times, but the film shies away from asking any questions about Hitchcock’s personal life (his wife Alma Reville is mentioned once). The personal is of no concern to Jones. He’s here to continue the conversation that Truffaut started 50 years ago, in which the French director argued that the British master of suspense was more than just an entertainer: he was an artist.

Carrying Truffaut’s torch, Jones enlists a whole new set of auteurs as talking heads: Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson, Olivier Assayas, David Fincher and others weigh in on the seminal value of both Truffaut’s book and Hitchcock’s work in their own maturations as filmmakers. Conspicuously, not a single female filmmaker is to be found in this movie; it’s as if Jones couldn’t think of even one who might have something to say on one of the most important directors of all time. This alarming gender imbalance aside, the results are mesmerizing to watch for two reasons: 1) it’s very obvious that every single one of these directors has long studied Hitchcock’s work and has insightful things to say, and 2) the visual splendors of Hitchcock’s work are used thoughtfully and masterly as a beautiful backdrop for those insights. Though Truffaut had a lot more to prove when he published his interview in 1967, back when cinema was only beginning to be taken seriously as an art form, Jones’ documentary proves its own value by underscoring the importance of continuing to value Hitchcock’s work, particularly the influence it’s had on more contemporary cinema. “Hitchcock/Truffaut” dips into the past to introduce the reasons for the auteurs’ original conversation and its cultural cache at that time, contextualizing the directors’ careers and respective backgrounds. Yet despite its historical subject, “Hitchcock/Truffaut” adeptly proves the timelessness of cinema.

Jones’ doc is about directors brought together by their love of cinema, and though Truffaut and Hitchcock operated in different worlds the film does touch on the effect they had on each other’s lives. Barbara Kopple’s“Miss Sharon Jones!” is about a tight-knit set of relationships, between soul singer Sharon Jones and her colleagues and friends, during her year-long cancer battle in 2013, which caused her band The Dap-Kings to take a break while she underwent chemotherapy.

The film follows Jones through her recovery, the scary follow-up tests that determined if the treatments were successful, and her glorious return as soul queen in 2014, with the release of the band’s new Grammy-nominated album “Give the People What They Want,” and their subsequent tour. This is very much a cancer survival story. We see how Jones deals with the most grueling aspects of the illness, everything from the toxic treatments to the physical side effects, to the financial strain it has put on the band. But this is also a music doc, albeit indirectly. Thanks to its longitudinal focus, interviews with The Dap-Kings and assistant manager Austen Holman reveal what it’s like to be a musician today. What a bloody tough racket, especially for a band who has long cultivated a strong critical fanbase without the kind of ultimate financial success that could let them more easily mitigate life-changing events like Jones’ illness. (By the time the band is ready to get on the road again, one member has already left for a gig on one of the daily night shows.) The film is successful in making this more than just about Jones’ struggle, as it shows how the cancer affects every single band member, both on an emotional level as well as a financial one. That tension, between the band wanting to make sure their mama queen is okay, and wanting to ensure they can get back to working as soon as possible, is thoughtfully explored by Kopple. The film doesn’t walk on eggshells with its subjects; nor does it seek to sensationalize them, either.

Yet the film’s real success lies in having Jones as its primary subject, and that’s because she’s a wickedly funny, fierce, phenomenal force of nature, a positive, vivacious character whose generosity and charisma touches every single person. Despite the countless stresses she faces during her medical struggle Jones remains strong and positive, neutralizing the terror the cancer would normally cause in those around her, and inspiring them to stay strong. Each time one of the subjects is about to break into tears while being interviewed in the film, you can’t help but see the positive difference Jones has made. As weepy as that sounds, the film never verges into sentimental territory, thanks to its perfectly paced moments of levity and positive energy, seen in small moments, like Jones’ jubilant discovery that she has been invited to guest on Ellen, one of her favorite daytime TV shows, or her making fun of the wigs she’s trying on early in her treatment process.

At the public screening of “Miss Sharon Jones!” at TIFF, the singer announced that her cancer had returned and that she wasn’t giving up the fight, not one bit. Here’s hoping that this beautiful, touching documentary reaches enough people to create new fans in Sharon Jones and The Dap-Kings, and gives the band the financial success they’ve always deserved.