A comprehensive look at the life of the influential 1960s singer-songwriter, Amy Berg’s“Janis: Little Girl Blue” follows the typical narrative structure of tortured-artist documentaries. Though it veers close to the edge of sentimentality a few times, the film proves to be thoroughly empathetic of Joplin as a musician, and, more importantly, as a person. Starting with Joplin’s rough beginnings as an outcast in her small Texan town of Port Arthur and her burgeoning interests in music, the film is excellent at documenting the singer’s interior life, using personal film footage and photos, interviews with family members, friends, lovers and colleagues, and hazy, sleepy-sounding voiceover narrations from her painfully honest diary entries (voiced by the equally groovy singer-songwriter Cat Power).

Berg wisely charts Joplin’s emotional developments in tandem with her professional ones, which creates a well-rounded picture of Joplin. Unfortunately, this kind of intimate picture fails to account for Joplin’s importance as a musician, despite the film contextualizing the revolutionary cultural milieu Joplin and her band, Big Brother and the Holding Company, found themselves in. That is to say, this is not the kind of picture that focuses so intently on one’s personal life that it can’t make room for broader conversation, and that’s quite necessary for a musician as important and overlooked as Joplin. We only get a very small glimpse at the legacy she left behind in the closing credits, when the film interviews people who didn’t know Joplin like Melissa Etheridge and other female musicians, who speak of Joplin as an inspiration and a feminist icon. That she was the first woman to prove her gender could “rock and roll” just as well as the men was of great significance, but it’s not something the film is interested in exploring.

Many people know at least vaguely of Joplin’s young death, but it’s the little details that we learn in Berg’s doc that allow us to truly admire who Joplin was as both a musician and a person. In Mina Shum’s “Ninth Floor,” on the other hand, we are given a detailed look at a forgotten slice of history: the 1969 Sir George Williams University racial riots in Montreal, which revealed the big, ugly, racial tensions and prejudices in Canadian institutions. Shum’s film, made through the National Film Board, faces a similar problem as Berg’s, in that it focuses a bit too much attention on its subject, which restricts Shum’s ability to say anything meaningful outside of it, about why her subject matters, and why it’s worth filming in the first place. The case of “Ninth Floor,” however, is a little different, because Shum is not documenting a famous musician—she’s telling the story of the Sir George Williams Affair, one of the most notorious student uprisings in Canadian history, a tale that few outside of the country know well.

That story begins in the late 1960s, when a complaint made by several black students at Sir George Williams about a white professor who was openly discriminating against them, went unnoticed. The school administration waffled over the issue for months, accomplishing nothing. In January 1969, a peaceful sit-in protest about the lack of resolution turned ugly, with people destroying the school’s computer data, one person setting a fire, and students being locked inside the smoke-filled ninth floor by incompetent riot police, as crowds outside yelled, “Let the niggers burn.”

The story is a shocking and important one, no doubt, especially in this day and age. However, why bother making a documentary and keep it purely factual when you could (more easily, and cheaply) write a really sharp article? That is unless you have something more to say on the subject. “Ninth Floor” gives us a very cursory yet damning account, featuring interviews from those same black students, who say they were forever changed after hearing people demand they be burned inside. And occasionally, “Ninth Floor” gets close at revealing a larger story about racism in Canada. For example, the subjects discuss their first impressions of Canada as being a welcoming country thanks to Montreal Expo 67, a perspective that quickly changed with their experiences in the classroom. A younger black Canadian student describes how racism has changed from being explicit to implicit, and how it remains dangerous and troubling. These are all solid moments, but “Ninth Floor” could have used more of them, and for an 81-minute movie, far too much time is spent painstakingly laying out every single detail of the original complaint and the riot.

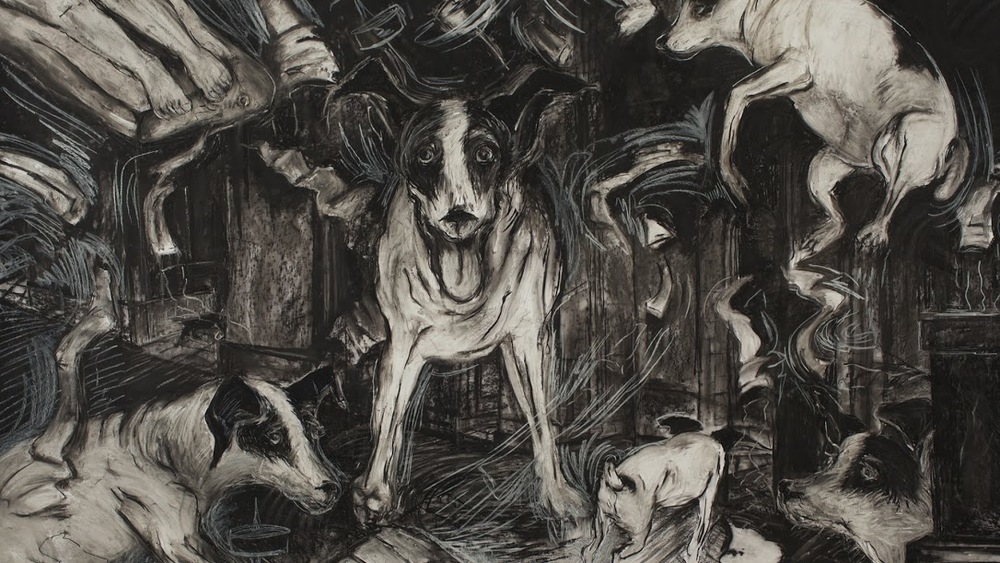

Where Shum’s doc examines a historical tragedy that has rarely received the film treatment, Laurie Anderson’s “Heart of a Dog” explores a well-documented trauma: September 11. But it comes from a very personal perspective, from the musician/performance artist’s very own, and it’s part of a larger video essay about loss, with 9/11 only figuring in as an authentic backdrop as Anderson documents the life and death of her rat terrier Lolabelle. It’s an event that has clearly left its mark on this New York artist. The growing surveillance culture that has developed in the last fourteen years is something that can be commented on without delving into more political territory; here, Anderson is interested in personal paradigm shifts, both within people and even dogs, like the ones trained to help with post-9/11 law enforcement.

“Heart of a Dog” is an impressionistic and lyrical meditation about memory, grief, loss and love, one that is prone to constant interruptions, digressions and flights of fancy. It’s a risky film because such personal expression, particularly those accompanied by animation and free-flowing thought, can be prone to solipsism. But here, Anderson is anything but. She’s poetic, she’s insightful, and her descriptions of her dog, who went blind and whom she taught to “play” the piano, are at once loving, amusing, and spiritually connected to deeper ideas about grief. Other reviewers have pointed out that Lolabelle could be a metonym of sorts for other losses Anderson has faced, including those of her husband Lou Reed and her mother. It doesn’t really matter if that’s true, because her tribute to Lolabelle has a sublime, simultaneous effect of being both so specific about her pet and also being universal enough to apply to any kind of loss.

Using animations, her own sketches, old and new footage, and photos that are frequently warped onscreen to match the speed of her rhythmic voiceover, Anderson offers one of the best films of the festival—and certainly the most interesting and innovative one in TIFF’s doc programme. You’ll probably love this film, whether or not you’re a dog person.