Does anyone deserve hagiography? If biographers are ethically bound to provide as well-rounded a portrait of their subjects as possible, what happens when they profile people who are virtually flawless?

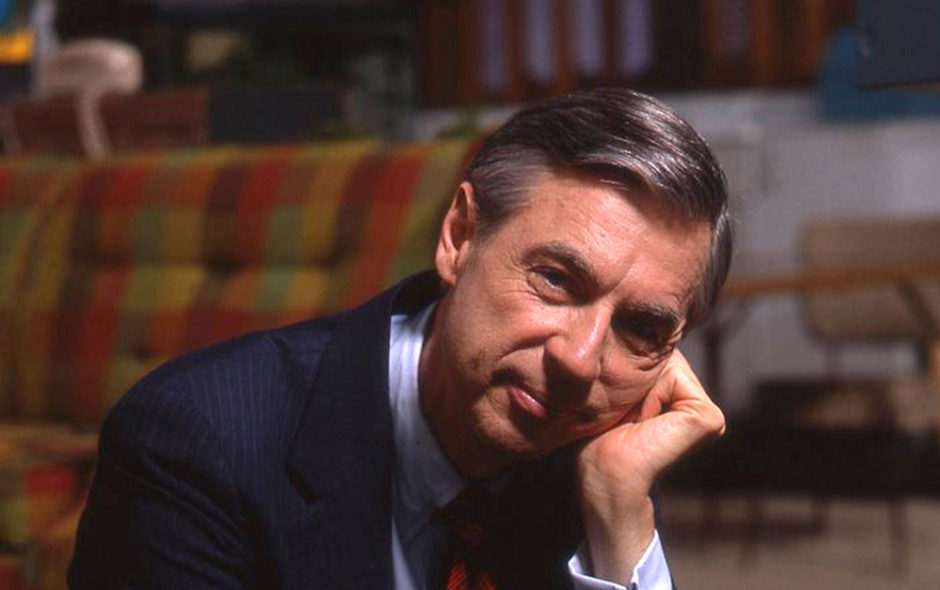

Saintly figures like Mother Teresa, Gandhi, Jesus make the job of biography challenging – and so, it turns out, does Fred Rogers. Documentary filmmaker Morgan Neville rounds out his film on the legendary performer in Won’t You Be My Neighbor? by exploring the psychology of the gentle Presbyterian minister who found his spiritual calling as a televised best friend for millions of children from the late 1960s until 2001 on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood.

This psychological and philosophical approach to Rogers was likely inspired by the man himself, as the film informs us that the minister was not only well-versed, but a participating thinker in the psychology theories of childhood development in the 1970s. Neville documents Rogers’s life without resorting to effusive praise and, in turn, makes a wonderfully empathetic film that doesn’t become sentimental — it captures the same principles that Rogers espoused.

Neville understands the need to explore why Rogers was so radiant and positive, his authentic persona so disarming it seemed impossible to believe. Indeed, one segment deals with backlash over his show, including comedy sketches that imitated Mister Rogers Neighborhood, various rumours about how he was supposedly a Navy seal escaping a dark past, clickbait thought-pieces that criticized the public harm of a children’s show that did the radical act of teaching love and kindness, and how Rogers’s attempts to teach children about political events — like Robert Kennedy’s assassination and 9/11 affected Rogers personally.

By including criticisms, one might think the purpose is to feel sympathy for the subject, but instead, it demonstrates that the world didn’t know how to respond to Rogers. Though the film glosses over details about his upbringing — he suffered from childhood illness, was bullied and very lonely, according to his mother, one of several family-member talking heads — Neville suggests the unoriginal but true idea that one of the most positive people who ever lived learn how to work through his anger and sadness.

Previous interview footage with Rogers (who passed away in 2003), some dating back to the 1960s with black-and-white film, inform us of this psychology. In an interview, the entertainer describes that, from a young age, music became an outlet to process negative feelings. The conclusion is that Rogers understood early on (and was gifted with safe, healthy parenting) that art could help one deal with emotions so that they didn’t have to take it out on anyone else.

The show’s cast and crew provide some colour and funny anecdotes — one crew member recounts silly pranks they’d play on set, and how he took a picture of his bare buttocks with Rogers’s still camera. Neville has plenty of footage to play with, but the weakest part of the film is his decision to juxtapose the media visuals with simplistic animation. An adorable cuddly tiger (not unlike Bill Watterson’s Hobbes) is intended to represent both the puppet Daniel from the series, as well as Rogers’s inner child. On one hand, it works, as the film articulates how Daniel and other puppets functioned as alter egos for the entertainer to express things he couldn’t say himself. But the animation simplifies and makes too neat a visual motif for the breadth of Rogers’s life.

Won’t You panders to the mainstream with its use of documentary tropes, but despite the conventional approach, the film finds ways to convey the unique profundity that Rogers gifted to generations of children through his simple yet effective philosophy in children’s entertainment.