In 1968, a new NFB program started using film to amplify the voices of marginalized communities

Originally published on CBC Arts (February 24, 2017).

In 1968, it dawned on the National Film Board that it was time for films about Indigenous people to actually be made by Indigenous people. This decision was first developed through the Company of Young Canadians, the Canadian equivalent of the U.S. Peace Corps, and the NFB’s Challenge For Change (CFC) program, an activist documentary project that ran from 1967-1980. The project produced a large body of work that focused on social issues and marginalized communities, and was inspired by the idea that film could be used as a medium to spark discussion between authorities and communities.

Challenge For Change led to some lasting developments — inspiring the model for public access television, for example, and creating a wealth of discourse about the ethics of documentary filmmaking. But the CFC also embodied a utopian vision of cinema as a tool for mobilizing social change that could never live up to the rhetoric, and some of the bureaucracy’s decisions regarding the CFC were problematic — the least of which was the idea that CFC members, being in positions of power and privilege, could best represent marginalized peoples themselves.

Earlier films made about Indigenous issues through the CFC, like Indian Relocation: EIliot Lake and Cree Hunters of Mistassini, led to new ideas on how to represent the points of view and voices of film subjects. While the importance of self-representation in media is well-accepted today — as evidenced by our conversations about Hollywood’s lack of diversity, for example — back in the 1960s, the idea of giving marginalized people filmmaking equipment was much more radical. In 1968, intensive workshops for young Indigenous people from across the country formed the inaugural Indian Film Crew (IFC) — and while some CFC members, like George Stoney, felt the workshop program’s implementation was clunky and ill-advised, there’s no doubt that some tremendously important and eye-opening documentaries came about as a result of the creation of the IFC.

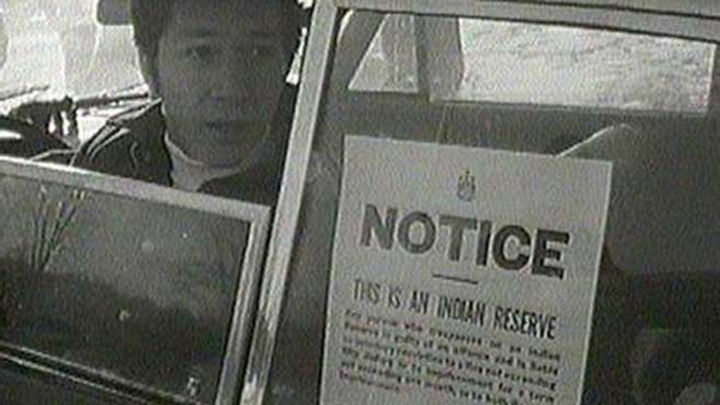

One of these films, produced by Stoney, is 1968’s You Are On Indian Land. Directed by Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell and Mort Ransen, the black-and-white film documents the demonstration by the Mohawk of the Akwesasne Reserve near the bridge dividing Canada and the U.S. near Cornwall, Ontario, in which protesters blocked the bridge to draw attention to the violation of their treaty rights. The protest’s set-up, confrontations with the police and consecutive rounds of arrests are caught on a roaming camera that adopts the direct-cinema style of documentary filmmaking.

It’s one of the most poignant films made by the NFB, and its dissemination through community screenings had a powerful impact on the very events it was addressing, including attempts to show the film at the trial. How the film came together is remarkable, too. CFC films required a fair degree of planning and preparation beforehand — being an extension of a bureaucratic institution likely didn’t help in expediting production. Mitchell, a young chief of the tribe who helped lead the protest, asked Stoney for a film crew the day before the protest. Despite the short timeline, Stoney was able to pull things together in less than 24 hours. It wouldn’t have normally been possible, but Stoney, an American documentarian who was new to the NFB, didn’t understand proper protocol and used this outsider status as a way to circumvent restrictions.

Unfortunately, cuts to the Company of Young Canadians eventually led to the dissolution of the Indian Film Crew in the 1970s. One of its members, Noel Starblanket, wrote frankly of his frustrating experiences in a CFC newsletter: “We are deeply interested in this communications medium and have discovered that we are dealing with a powerful outlet for emotion and a power that even administrations recognize…But we may not be able to carry on our work with full independence. Our future is not assured. Is a strong, independent voice for the Indians worth supporting?”

The answer of course, should have been yes, but it took a while for the NFB to catch up. While the IFC did not last, the program had a lasting legacy on the importance of Indigenous voices in Canadian filmmaking and helped instigate future projects at the NFB to represent Aboriginal perspectives, including Studio One, the Aboriginal Filmmaking Program and First Stories. These programs have helped fund the works of Indigenous filmmakers like Alanis Obomsawin, Gil Cardinal and Neil Diamond — who are carrying the torch and inspiring a new generation of voices today.