Even the most sensitive animal lover would admit that John Wick’s premise—an assassin kills dozens of men as he tries to get to the one who killed his dog—sounds a little silly. Though pets are beloved companions in real life, they’re low-stakes territory in most fiction: In cinema, viewers are rarely asked to take animals seriously. Pets are typically killed, run over, or lost; they become visual background fodder, occasionally employed to signify that an owner is crazy or alone. In some painful instances, they’re endowed with CGI maws and silly voices. But John Wick—which ended up as a fairly well-received action-thriller—proves that virtually any premise can be turned into a decent film and taken seriously, given the right elements, like strong direction, good performances, and an enticing script.

The same can’t be said of Murder Of A Cat, a frivolous noir spoof by first-time feature director Gillian Greene. At first glance, the film could be mistaken as a coincidental parody of John Wick. When Clinton (Fran Kranz) sees the corpse of his cat, Mouser, outside his mother’s suburban home, with a brightly colored crossbow arrow sticking out of its side, he’s upset and delusional enough to expect a full police investigation. But Sheriff Hoyle (J.K. Simmons) is more interested in dating Clinton’s mother Edie (Blythe Danner) than finding Mouser’s killer.

So Clinton, a man-child living in his mother’s basement, takes the feline felony into his own hands. His amateur sleuthing leads to multiple dead-ends—which, given his lack of socialization and intelligence, he misinterprets as clues—but eventually his conspiratorial tendencies and stubbornness uncover another crime entirely, a retail racket involving Ford (Greg Kinnear), a department-store owner who resembles an unhinged Ned Flanders, and whom Clinton is convinced is Mouser’s murderer. Clinton also discovers why Mouser used to go missing for days at a time: his polyamorous cat was moonlighting with a second owner, Greta (Nikki Reed), a pretty femme-fatale type who quit her job as assistant manager at Ford’s when she uncovered her boss’ illegal scheme. Rounding out the cast is Yi Kim (Leo Nam), a skeevy, unpredictable Ford’s staffer, tasked with the unfortunate role of playing the weird Asian dude who does magic tricks at inopportune times. (Technically, any time is a bad time for magic, but Yi Kim makes a good case that some moments are worse than others, like after being brutally hurt.)

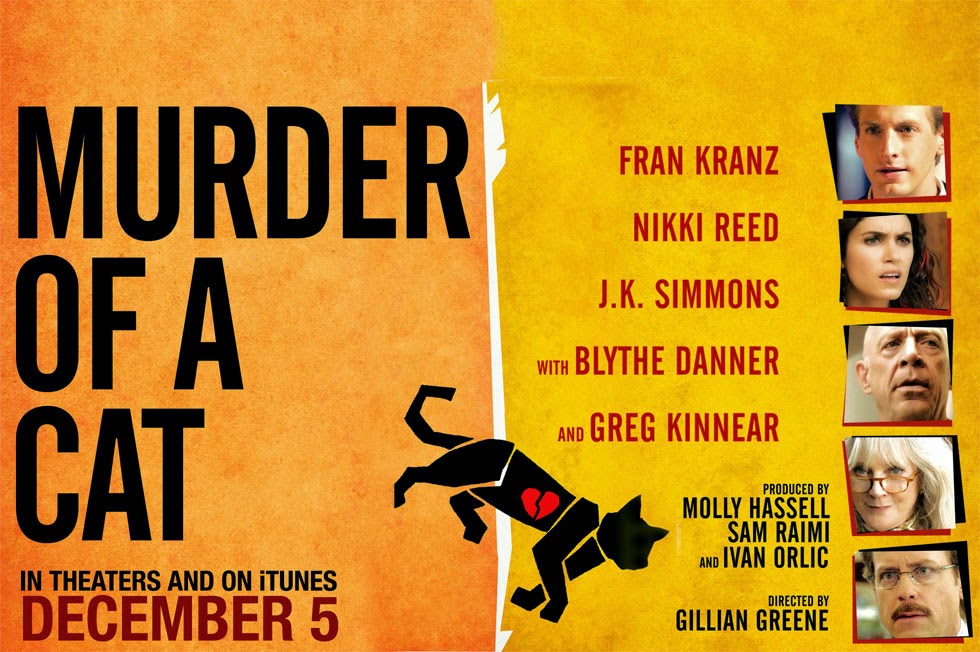

The story is silly and lopsided, but that doesn’t have much to do with the cat-murder. Kranz fails to make his infantile character endearing—Clinton is more boring and boorish than precocious—and as the protagonist, he spends a lot of time onscreen. His shaggy haircut is an obvious indication of his inability to grow up, but it’s clearly and perhaps even intentionally a wig; there’s also his continuous stream of grandiose delusions about someone being out to get his cat. Kranz’s performance is more suited for a sketch-comedy scene than a feature-length film, and the character’s sudden, unexpected growth into adulthood at the end of the film (particularly his romantic involvement with Greta) is implausible and corny. The charade is made particularly ridiculous by the film’s unceasing score, with generic saxophone-jazz tracks that might be expected in an animated noir parody akin to Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Most of the noir references are slight and specious, including Clinton’s handmade action figure, named Doghouse Reilly, and the film’s poster, a send-up of Anatomy Of A Murder that features a cat block outline. Occasionally, Clinton references crime-movie terminology—like calling Ford a “fence”—and it borders on funny without actually producing guffaws.

All of this is a shame, because Murder Of A Cat seems to have everything going for it: comic veterans like Kinnear and Simmons, a Hollywood Blacklist screenplay, and given Greene’s marriage to Sam Raimi, the showbiz connections that can help give a movie extra marketplace clout. But it turns out that some of those alliances backfired. Greene has directed Kranz before (in her short “Fanboy”), and her assessment of his strengths doesn’t jibe with Clinton’s character, which requires a more offbeat tone of comedy than Kranz’s straitlaced version of dorkiness. Greene’s misinterpretation extends to the entire film more generally. The script for Murder Of A Cat is undeniably funny at times, a potential cross between Ace Ventura andThe Big Sleep. But Greene misses multiple opportunities to make that humor palpable, proving that film comedy is as much a tone as it is a performance, requiring a strong directorial vision to make it pitch-purrfect.