Is there no more playful symbol of 1980s globalization than the Leningrad Cowboys? Started as a joke project between director Aki Kaurismäki, Sakke Jarvenpää and Mato Valtonen in 1986, the Leningrad Cowboys soon gained fame for the Kaurismäki-directed music videos “Rocky VI,” “Thru the Wire,” and “L.A. Woman.” Kaurismäki was convinced (correctly) he had a phenomenon suitable for a feature film on his hands, which led to the making of Leningrad Cowboys Go America, a road movie in which the fictitious band leave their Siberian homeland after their manager is convinced they can make it big in America. The success of the film convinced the Leningrad Cowboys to begin touring and releasing albums as a real band, which they do to this day.

At first glimpse the band’s silliness is paramount. Their blank expressions, bloated number of band members (including a frozen dead one), tyrannical band manager Vladimir, and freakishly large Winklepicker shoes and even larger pompadours are all part of an ostensibly fantastical creation befitting the music-mockumentary genre. But what started as a joke between friends grew into a genuinely resonant depiction of cultural assimilation and a gentle critique of the American Dream, serendipitously tempered by Kaurismäki’s trademark deadpan humor. Equally genuine, as can be attested in the film, is the band’s shared passion for music.

Early in the film, the Leningrad Cowboys arrive in New York, having mastered the English language through language books on the flight over from Europe (“Spinglish! I mean, Speak English,” commands Vladimir). But in America, where they were told anything goes, they are pressed for luck. A booking agent gives them a shot but then tells them to get lost, his veteran ears unimpressed by their hokey polka. He does, however, promise Vladimir a gig in Mexico, for a relative’s wedding. “Your music will go over big down there. Here we have something different. It’s called rock and roll,” he explains helpfully. This early on in their career, the few listeners that have given the Cowboys a chance appear only capable of redeeming their performance by compartmentalizing it in their schema of “world music,” which they believe must only be interesting to other parts of the world.

Vladimir’s decides that in order for the band to succeed in America, they must learn how to play rock and roll, which they do at a comically fast rate, the internal logic of the film long having been thrown out the window in order to make room for the wooden coffin containing their dead band member. (Or perhaps the film is suggesting that the learning curve for rock is nonexistent?) As the Leningrad Cowboys move deeper south into the U.S. on their way to Mexico, they perform at bars and lounges, adapting to the local tastes of each town with every set, breezily absorbing a variety of American music styles. They start – naturally – at the birthplace of rock and roll, Memphis Tennessee, belting out a swinging, sax-infused cover of “Rock and Roll is Here to Stay.” In New Orleans, Louisiana, their cover of The Champs’ “Tequila” is warmly embraced by the crowd, but they find less success appealing to the rednecks at Joe’s Place in Houston until their American-born cousin leads them into a raucous rendition of “Born to be Wild.” Along the way, the band faces numerous obstacles: a short-lived mutiny against Vladimir, a makeshift funeral procession for their dear dead friend that ends with their mass arrest, a jail stint cut short when the guards go crazy from the Leningrad Cowboys’ incessant drumming, cars sold to them by the likes of Jim Jarmusch (in a cameo appearance), the thawing-out and resuscitation of their dead friend upon having tequila touch his lips, and the eventual and long-awaited performance at the Mexican wedding, by which time the Leningrad Cowboys have perfected their mastery of other music genres, confident in backing a Mexican singer through traditional songs. While the Leningrad Cowboys primarily perform straightforward covers, there remains the whimsical pomp and seriousness of Eastern-European folk music in each performance.

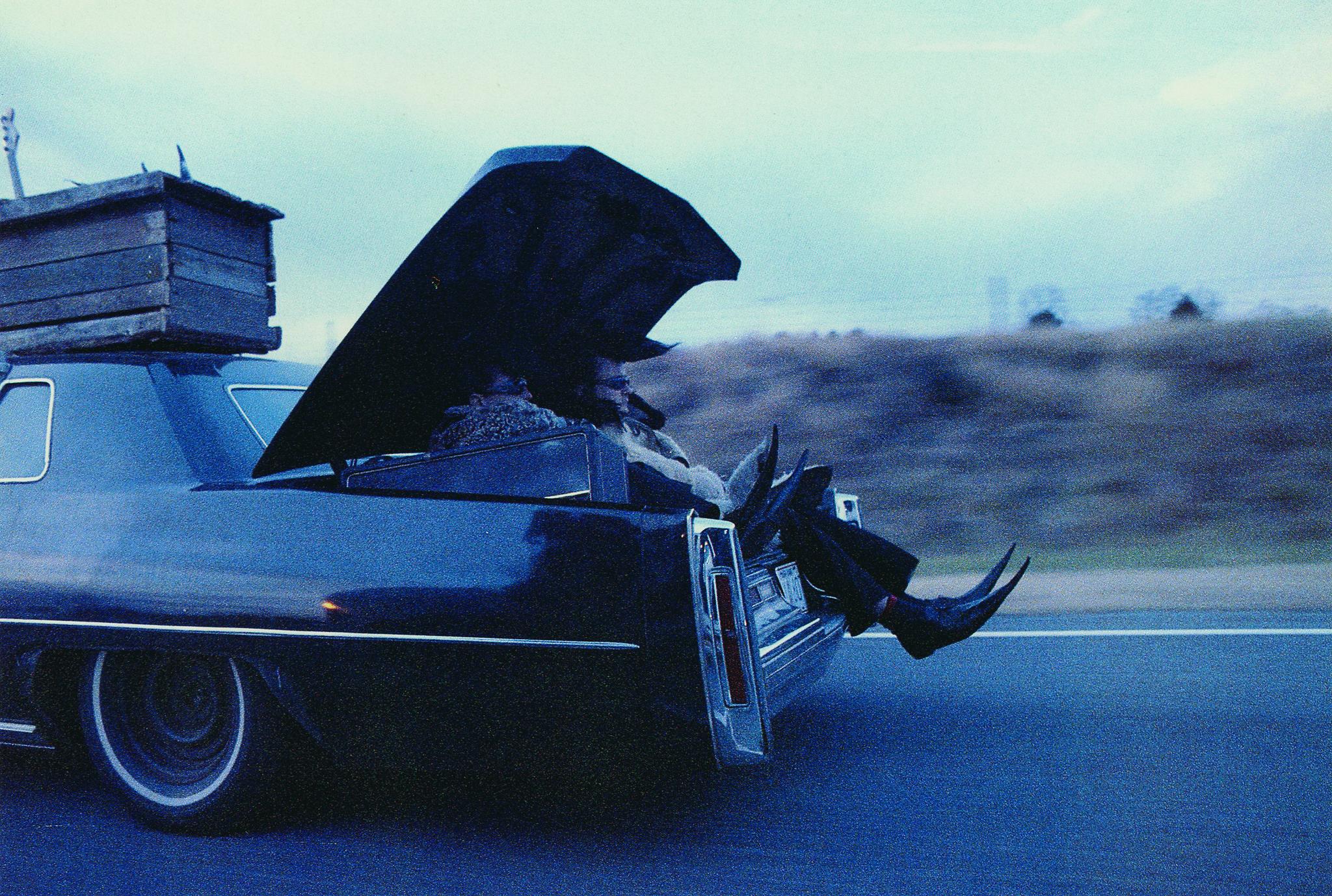

They may have exchanged their accordions for guitars, but the Leningrad Cowboys would never pretend or want to be American cowboys. The band and their journey to America are grounded on the idea that one’s cultural character can adapt to new surroundings without needing to sacrifice integrity or authenticity. Kaurismäki underscores this point comically—for one thing, the Leningrad Cowboys’ pompadours and shoes have nothing to do with East Europe, but they do forge an unforgettable, if not absurd visual motif. While they adapt musically, the band is less capable in grasping more common-sense elements of Western culture, sometimes interpreting English phrases too literally, as in the hilarious scene where Vladimir feeds his doggy bag of a restaurant steak dinner to an actual dog, while the hungry musicians look on. Cultural assimilation is a constant struggle in compromise. Take, for example, Vladimir’s decision to buy the most expensive car on Jarmusch’s lot: a Cadillac, which he promises Vladimir is strong enough to survive World War III. This is a comforting thought for Vladimir, who purchases the automobile with all the money in his pocket, not realizing it doesn’t contain enough seats for all the band members. Here, desperation and creative problem solving leads to a Siberian version of Pimp My Ride: two car seats are easily installed in the trunk.

Holding onto certain remnants of one’s homeland – be they a fur coat, family hairstyle, or frozen bassist – is not necessarily a defense mechanism, but a means of defining one’s character and identity. In the case of the Leningrad Cowboys, that character is emboldened through the solidarity of band regalia. The band may have attained a certain degree of success in the country of opportunity – against all odds – but they would never give up their pompadours or shoes to fit in.