Last week was a tough one for Canadian film, bringing the deaths of two important filmmakers one after the other. Colin Low and Don Owen were several years apart in age and differed in their style and approach, but both played a fundamental role in defining Canadian cinema with their work at the National Film Board (NFB).

“Art, but for whose sake?”

Gary Evans, historian, characterizes debate around the NFB in the ’60s

The documentary film began to change dramatically after the era of propaganda war films, which were pioneered by Scottish filmmaker John Grierson (who also helmed the creation of the NFB). The medium had become stagnant, boring and forgettable. Change was needed — badly. The advent of mobile camera and sound equipment (some of them technologies created in-house by NFB technicians) allowed young documentarians like Low and his contemporaries Roman Kroitor and Wolf Koenig to shake things up radically.

In 1954, Low was anxious to finish his new documentary, Corral, to meet a strict government deadline. The young filmmaker was happy with how things were working out. He had shot some arresting handheld footage of an Albertan cowboy lassoing mustangs, which contrasted from the typical iconography of the Western cowboy. The score, by Eldon Rathburn, poetically aligned with the film’s fluid, fast rhythm. The only thing left to do was write and record the voiceover narration. Low left that up to Stanley Jackson, his peer at Unit B, which comprised a tenacious group of NFB wunderkinds (including Norman McLaren). Jackson promised to finish it over the weekend.

An expectant Low and supervisor Tom Daly arrived on Monday, eager to see the final product. “It’s done,” Jackson said.

Gathered around the moviola, the crew watched the film; it was silent, save for the music. “Where’s the commentary?” someone asked halfway through. They kept watching. When it was over, Jackson asked them frankly, “What would a commentary do for that?”

Low and Daly couldn’t help but agree. Corral became the first NFB film without a voiceover track. This was a cutting-edge artistic choice at the time, as some NFB members, for example, thought people were “expected to be told what to think about pictures.”

Corral by Colin Low, National Film Board of Canada

Others at the film board were less narrow-minded, and many of these artists found themselves working at Unit B. The team was an anomaly at the NFB. Its members were inspired by the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, and wanted to translate the French photographer’s vision to celluloid. These film artists were frequently young, male, and Anglo-Saxon. The NFB changed their hiring practices to be more diverse in subsequent years, hiring First Nations filmmakers and more women, for example, but in the early 1960s, diversity was the least of Unit B’s concerns. Their filmmaking experiments were lambasted regularly by NFB and government officials, who didn’t quite understand why taxpayers should pay for the capricious experiments of a few young intellectuals. Film historian Gary Evans succinctly summed up the ideological debate about what kind of films the NFB should be making. “Art,” he wrote, “but for whose sake?”

History proved the naysayers wrong: Unit B won awards and garnered recognition around the world, including the attention and respect from American auteurs Stanley Kubrick and George Lucas. The team helped forge the direct-cinema and cinema vérité movements. Its films continue to play a culturally significant role in Canadian cinema.

Low and Kroitor landed their opus with Universe in 1960. The educational film depicts outer space in then-groundbreaking fashion, and it became a major influence on Stanley Kubrick. Some of the techniques that Low and Kroitor invented — while going tens of thousands of dollars over budget — were used on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Low declined Kubrick’s offer to work on the film, but Kubrick managed to secure the documentary’s narrator, Douglas Rain, to voice the film’s villainous robot Hal, and Wally Gentleman, who did optical effects on Universe and built the model spaceships for 2001. NASA itself bought over 300 copies of Universe, and it remains one of the most successful educational films in Canada.

Universe by Roman Kroitor& by Colin Low, National Film Board of Canada

Kubrick and Lucas were particularly inspired by the experimental gems of Unit B filmmaker Arthur Lipsett. Kubrick wrote to Lipsett about his Very Nice, Very Nice short, claiming it was “the most imaginative and brilliant uses of the movie screen and soundtrack that I have ever seen.” Similarly, Lucas said Lipsett’s 21-87 was “the kind of movie I wanted to make — a very off the wall, abstract kind of film.”

Unit B’s early successes may partially explain why its filmmakers were given more creative freedoms — like going over budget and over schedule — than other NFB filmmakers. Don Owen took full advantage of these freedoms in Unit B’s final years.

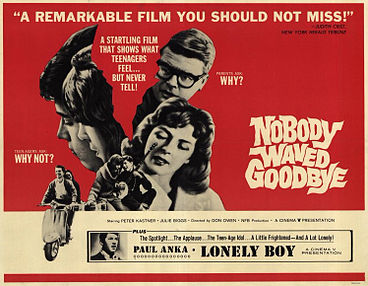

He pitched a short short docudrama about juvenile delinquency under the working title First Offence. What he made instead was Nobody Waved Goodbye, a nihilistic coming-of-age story about a troubled, middle-class young man. Scenes were largely improvised and offered a fascinating blend of documentary realism and fictional dialogue—both novelties at the time.

Nobody Waved Good-bye by Don Owen, National Film Board of Canada

Speaking to the media, Owen brashly claimed to have gone over the management’s head by ordering more film stock than would have been deemed permissible. This was during the summer, when execs were away.

At Parliament, MPs were quick to pounce: Why was the NFB, an organization intended for making documentaries, creating theatrical works of fiction? Why didn’t the higher-ups know anything about it? Whether or not the latter accusation was true, the NFB nonetheless denied the allegations and allowed Owen to reshoot scenes in order to finish the film.

Good thing they did: Nobody Waved Goodbye essentially started the English-Canadian industry as we know it today.

Good thing they did: Nobody Waved Goodbye essentially started the English-Canadian industry as we know it today.

Outside of a few barely remembered features made by Nell and Ernest Shipman in the silent era, English Canada had virtually no history in making feature-length fiction films until the 1960s. Alongside its NFB-funded French equivalent, Le chat dans le sac, and other 1960s classics like Bitter Ash and Goin’ Down the Road, Owen’s debut helped incite a revolutionary dialogue about the importance of feature-length filmmaking in Canada — and why it should be funded.

In 1967 the government started the Canadian Film Development Fund (now Telefilm Canada), which provided a new financial avenue for feature-length films. Today, multiple generations of Canadian filmmakers have benefited from Telefilm’s funding and gone on to win even more international acclaim for our national cinema. Such is the lasting legacy of Unit B, an aesthetic incubator funded by the government and allowed to exist only briefly. It gave Owen and Low the power to bring their cinematic visions to life, and to inspire those who followed in their footsteps.