Jafar Panahi’s harsh sentence from Iranian authorities—his house arrest, restrictions on filmmaking and travel, and communicating with media—have forced the filmmaker to contemplate not only the intellectual struggle that accompanies tyrannical artistic censorship, but its combined psychological and emotional manifestations. Having been denied the professional and creative outlet that made him an internationally appraised director, Panahi is now understandably enveloped in a kind of existential crisis, an unimaginable experience that he’s nonetheless found a way of crystallizing into his two latest films, made illegally with the help of other filmmakers. These works—2011’s This Is Not a Film and this year’s Closed Curtain, co-directed by Kambuzia Partovi—easily surpass Panahi’s previous films in their aesthetic complexity, intellectual rigor, and, above all, reckless abandon. This Is Not a Film was a creative risk for Panahi because, as a so-called documentary, the film didn’t appear to be about much more than Panahi’s daily activities under house arrest: talking to his lawyer, pet-sitting his daughter’s iguana, and describing to the camera a script he wrote for a movie that he cannot make. Of course, Panahi’s seemingly candid setup transversed the conventions of documentary into a meaningful work of meta-cinema, a thorough exploration of the frustrating limits to which an artist can physically make a movie by simply turning on a camera and talking and walking through his or her ideas.

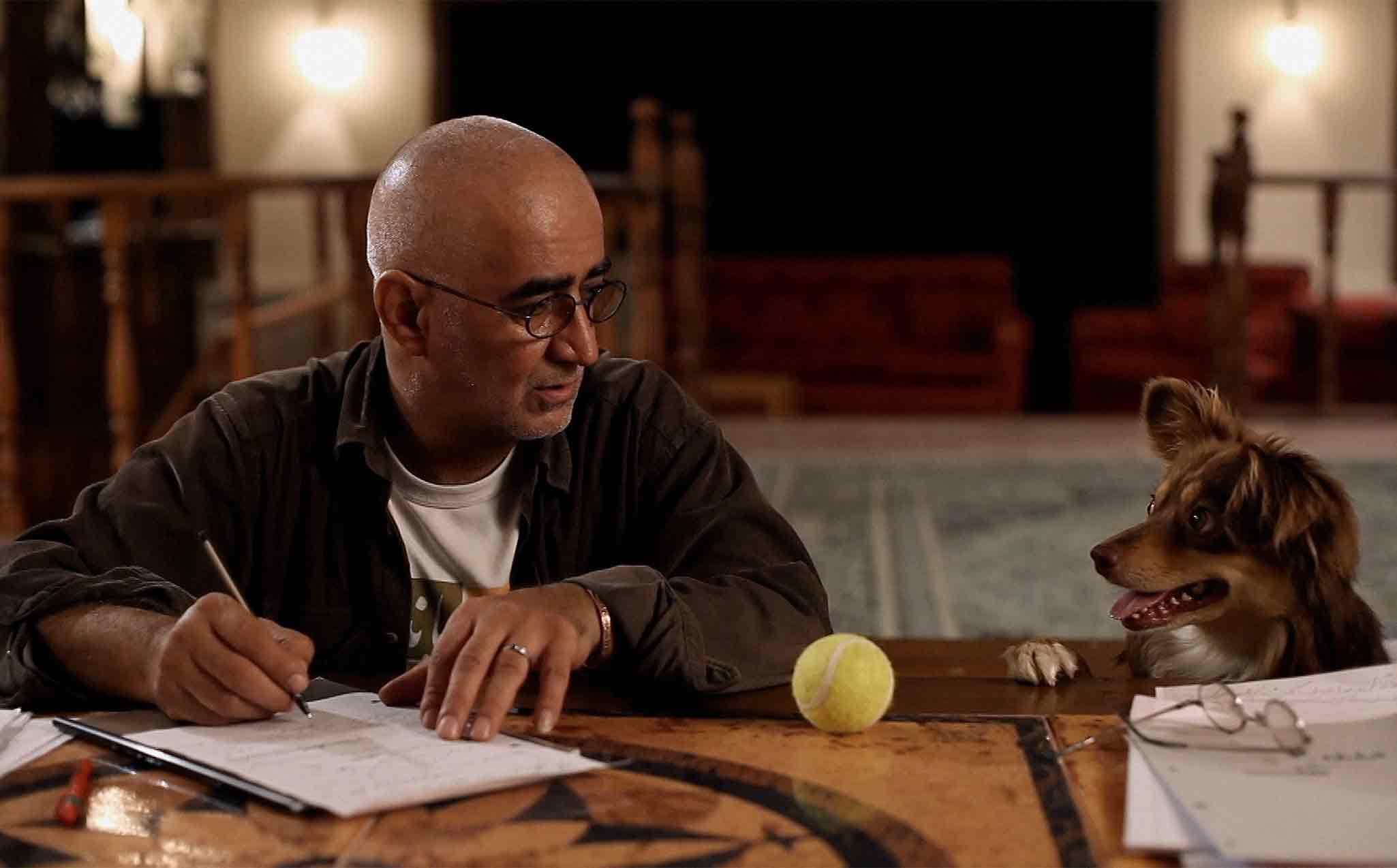

In Closed Curtain, Panahi has moved past only talking about his story ideas. The film opens in a well-constructed diegesis about a scriptwriter (Partovi) and his dog, but halfway through the film, Panahi suddenly appears. The curtains are figuratively and literally drawn, and the story deconstructs the stability of the world it’s been establishing as well as Panahi’s own psychological stability as a filmmaker; he can only take a few steps into a narrative before his impulse for self-reflexivity and self-doubt kick in. Instead of compromising the material at hand, this fourth-wall breakdown adds a layered sophistication missing from Panahi’s previous productions.

The film isn’t only self-reflexive, but also self-referential, opening and closing with static long takes of a barred window of a beach house. This framing is virtually identical to the immobile shots of a barricaded entrance of a jewelry store that open and close 2003’s Crimson Gold. The bars in both films—slender, elegant, and suffocatingly encompassing the wide cinematic frame—allude to the cognitive imprisonment of its characters. In Closed Curtain, that includes Panahi himself, but initially it’s Partovi’s scriptwriter, who arrives at the beach house with the nervous air of a man on the run. Once inside the safe confines of the large, empty house, the writer unzips a duffel bag to reveal an adorable, small dog named Boy. The writer is particularly concerned with Boy’s safety and won’t let him outside to pee—a strange restriction that makes sense once he turns on the television to show broadcasts of a public dog ban, which Boy watches disconsolately with his nose buried underneath the couch cushion. The ban, a religious decision based on the Islamic idea of cleanliness, seems allegorical, but it’s sadly very much rooted in reality. In Iran, dogs are regularly rounded up and euthanized, and owners no longer risk taking their beloved pets outside.

Despite his anxiety over Boy’s whereabouts, the Writer seems mostly at peace in the solitude of his beach house, though his decision to pin up black curtains over thin white ones already covering the windows seems excessive. Suddenly a young man, Reza (Hadi Saeedi) and his sister, Melika (Maryam Moqadam), appear at the door, urgently in search of refuge from the authorities. They counter the Writer’s suspicions about their motives with their own questions about his runaway status; it appears the Writer may also be a fugitive, but their terse trade-offs are largely ambiguous about the characters’ respective circumstances. Soon, Reza leaves to find a car, putting the apparently suicidal Melika in the Writer’s care, but after annoying him she leaves without a trace, only to magically reappear again the next day inside the house. Agitated by these developments, the Writer creates a safe space where he and Boy can hide, which he uses the next day when his house sounds like it’s being ramshackled by unknowns.

It soon becomes apparent that if these characters are on the run from anything, it’s from their own reality. These are phantoms, not fully formed characters, figments from the shattered mind of their creator. When Panahi appears in the frame, initially seen in a mirrored shot as he pulls down curtains that reveal posters of his previous films, illuminating that this is likely his own house, he has the same rigid, tense air as the Writer, and given their similarities (the fact that the character is played by the co-director and is living out his kind of house arrest), Partovi’s character is obviously a stand-in for Panahi himself.

Panahi walks around and tears off curtains and then makes tea for himself, pouring a few extra cups; now that he’s alone in the house, it’s uncertain who the cups are for. Neighbors visit and ask about the broken glass, and are tasked with replacing it, and their presence is jarring: Are they in the reality in which Panahi is making the movie, or are they in a separate diegesis altogether? The neighbors leave, the characters reappear, and then leave again. Panahi makes tea once again. Is the tea for the neighbors or for the characters? The film never answers these questions, or why or how Panahi is able to move from the world inhabited with his characters to the allegedly real one containing his neighbors.

Closed Curtain uses Panahi’s beach house to create a metaphysical reality in which he appears as much a political prisoner in his real life as he does within his creative world; the fantastical escape offered to him by his characters’ diegesis seems both restrictive and enticing. Melika invites him in a recorded iPhone video to follow him into the water to kill himself; she disappears into the ocean in the video, and we soon watch him start recording a video where he does the same. The film then rewinds the footage and he reappears, dry and unharmed. In Iranian postmodern art, the symbolic use of natural objects and places is an important motif in underscoring the sojourns of its characters, and there are few natural elements more symbolically powerful than the warm, seductive immersion of the ocean. Panahi’s symbolic journey won’t end with drowning waters, but in Closed Curtain he articulates exactly how warm and enticing the waters can be.