If you haven’t already read “The Uninhabitable Earth,” the haunting and widely shared New York Magazine article by David Wallace-Wells, you’re probably feeling fine. Blissfully ignorant. Happy, even. The article paints a not-so-pretty picture of how things will shake down over the next century as climate change alters Earthly ecology, where food shortages lead to massive starvation, temperatures rise so high the sun will literally cook people, and polluted air strangles us to death. One sci-fi-sounding factoid reminds readers of ancient diseases trapped underneath melting Alaskan and Siberian ice, or as Wallace-Wells puts it, “an abridged history of devastating human sickness, left out like egg salad in the Arctic sun.”

For all the apocalyptic foresight, Wallace-Wells’ prose doesn’t hold a candle to the imaginative ways in which Hollywood currently depicts climate change, or “cli-fi,” as the sub-genre is called. More often than not, cli-fi movies set boundaries to assuage any fears that its premises are realistic. They often take place in a far-off future that is reassuringly unfamiliar, employ far-fetched technology that we can only dream of, feature a small but cataclysmic event that preposterously ruins the whole planet, or end happily as the Earth magically returns to its pre-disastrous state, as if nature can be fixed with the flick of a switch.

In reality, climate change is more slow-moving and complicated — a single natural disaster can’t wipe out the entire planet — but it’s also more rapidly advancing than we think; humans have been roaming the planet for hundreds of thousands of years, yet half of our carbon footprint has been stomped into Earth in the last three decades alone. There’s an argument to be made that Hollywood should strive to be more eco-realistic. More so than finger-wagging documentaries (sorry, Al Gore), blockbusters reach the masses and, in theory, can casually compel uninvested people to take action. Here are five cli-fi movies that should scare you in an entirely new way:

The Last Winter (2006)

When one of its oil riggers has a freakish, fatal accident that cannot be explained, a research team in the middle of Alaska believes it’s being haunted by… something (not The Thing). A staff environmentalist offers a reassuring scientific explanation that the melting of arctic ice (due to global warming) releases methane, and the natural gas mixed with hydrogen sulfide is causing the workers to suffer from hallucinations.

But as more people die, a less-scientific, yet more likely alternative idea begins to emerge, one that is no less environmentally tinged: The ghosts of fossil fuels siphoned from the ground are wreaking vengeance on greedy humans. Larry Fessenden’s spooky film explores the Algonquian myth of the Wendigo beast, often associated with environmental greed, and while it may be the most supernatural film on the list, it’s eerily similar to the trapped-in-ice ancient disease epidemic that may await us in real life. The Last Winter is also one of the best in relaying a very obvious thematic message: Our pilfering of natural resources does not go unpunished by Mother Nature herself.

Happy Feet Two (2011)

Happy Feet is a beloved family enviro-flick that won the 2007 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film. Sadly, the movie’s sequel, despite the simple charms of dancing, singing penguins living in the Antarctic, earned negative reviews and disappointing box office numbers. So why is Happy Feet Two on this list instead of Happy Feet? Both are environmentally conscious films — the original angered many conservatives, including Fox News’ Neil Cavuto, who famously declared it far-left propaganda and that he “half expected to see an animated version of Al Gore pop up.” But Happy Feet 2 refines its environmental message to show, not tell, and is thus more exemplary of how a film can powerfully illustrate a personal story — in this case, one penguin’s fear of parental inadequacy — and use a social issue for situational context that gets people to care without hitting them over the head with the message or terrifying them. Beneath its plethora of bird-crap jokes and bad puns, Happy Feet 2 is a story about cooperation, an absolutely necessary component for penguins — or humans — trying to survive climate change.

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

The best film of 2015 was the newest installment in George Miller’s grungy Mad Max franchise. In this post-apocalyptic future desert, tyrant Immortan Joe’s draconian control over the water supply in the Citadel and imprisonment of his breeding wives is a damning but accurate portrayal of the patriarchy set in a post-nuclear apocalypse. But unlike Snowpiercer, a similarly high-concept, arthouse-action movie wherein few remaining commodities are fought over through distinct class divisions, Fury Road also tackled the concept of crushed optimism.

That’s what makes the movie interesting in the scope of cli-fi. Furiosa’s epic journey across the desert is supposed to end at the Green Place, an idyllic crop-growing land that survived the nuclear holocaust. Her group’s crushing realization that the Green Land has become a poisonous swamp thanks to soil contamination, makes Mad Max’s ecological themes more resonant. The film is not just about the tyrannical rule of scarce resources, it’s about our own naive misconceptions of taking nature for granted, and our subsequent demoralization in realizing what once gave us comfort no longer exists.

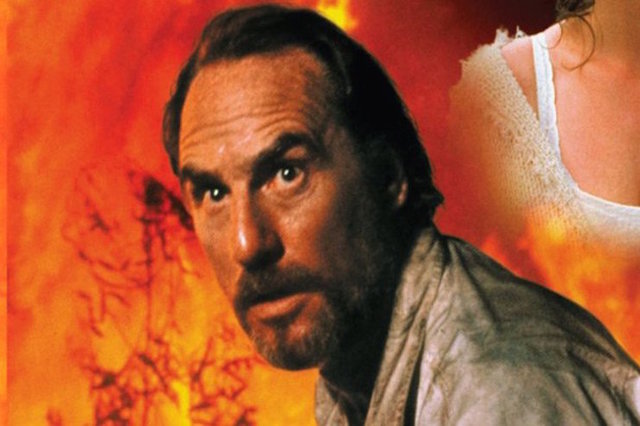

The Fire Next Time (1993)

This made-for-TV movie is outdated, over three hours long, and features soapy plots and characters — that’s all on top of hilariously gimmicky 21st-century technology. But the CBS TV miniseries might actually be the only cli-fi offering that comes remotely close to depicting our climate-change reality.

Set in 2017 (!), the two-part film follows a Louisiana-based family on their way to New York, one of the few regions in the country not yet devastated by constant droughts, floods, and hurricanes, the direct result of climate change. One scene features a TV interview with a real scientist who plays himself, Stephen Schneider, commenting on the lack of awareness and action in the previous quarter century in stopping the effects of global warming. Reviewed poorly — Variety described it as “glum” — and lacking the budget of a big Hollywood disaster movie, The Fire Next Time faded into obscurity.

The Day After Tomorrow (2004)

Disaster-movie specialist Roland Emmerich got some heat (no pun intended) from scientists upon the release of his blockbuster starring Dennis Quaid and Jake Gyllenhaal — but we can cautiously recommend it. According to paleoclimatologist William Hyde, the film is “to climate science as Frankenstein is to heart transplant surgery.” The ice age phenomenon seen in the film is a result of melting ice caps and a chaotic array of global super storms — in the realm of possibility, but not in its actual depiction, where a natural doomsday immediately transforms the world into complete chaos. While the film’s special effects were quite impressive for the mid-2000s, the over-the-top story spawned a slew of imitators that envisioned similarly quick descents into glacial epochs. And an audience-research study found that TDAT had mixed results in changing viewers’ perceptions of climate change; though it seemed to raise awareness of the issue, its apocalyptic setting confused them as to what they could possibly do to help.