Vincente Minnelli’s first masterpiece, Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), is not only an enduring classic in the director’s oeuvre but one of Hollywood’s best musicals. The film, the cinematic equivalent of a snow globe depicting a romanticized America in beautiful Technicolor, embraces nostalgia, but not without an undercurrent of darkness. This is his signature tenor, and though it first appeared in St. Louis, it’s been noted in Minnelli’s other works, even by critics who denounced the director as a stylist instead of an auteur—Andrew Sarris once described Minnelli’s “curiously depressing” tone in An American in Paris and Gigi.

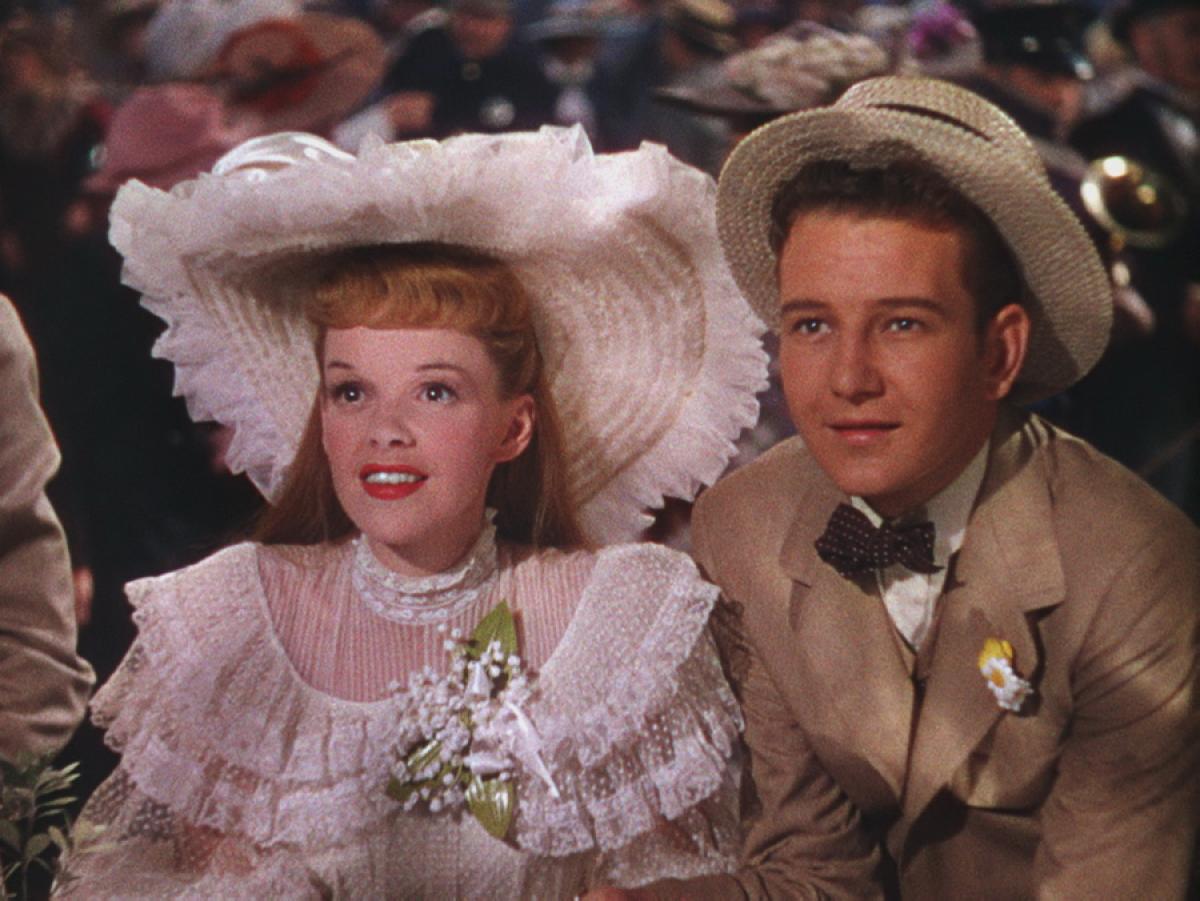

Minnelli began to hit his stride in the ‘40s with a succession of musicals that began with St. Louis. Though he’d met Judy Garland in a previous production, Minnelli fell in love with the then-22-year-old performer on the set of St. Louis. Though the real star of the film is Margaret O’Brien, who plays Tootie, the youngest, spirited daughter of the Smith family, Garland, who plays the teenage daughter Esther, was given special attention by Minnelli, and it shows. Minnelli hired makeup artist Dorothy Ponedel to devise a new look for Garland that would better accentuate her beauty. Garland appreciated Ponedel’s changes so much that the studio hired her for every film Garland did thereafter.

The story is about the Smiths, a middle-class family whose children, Rose, Esther, Agnes, Tootie and Lon. Jr., are eagerly awaiting the opening of the World’s Fair in their beautiful, burgeoning city. Their father, Alonzo, thinks he knows best, and their mother, Anna, is always eager to tell him when he doesn’t (which is often). A gallant grandpa and a tyrannical but caring maid, Katie, round off the ensemble. St. Louis could be read as a family drama/comedy that delights in wholesome American pastimes: servants finessing homemade catsup; kids dressing up for Halloween and facing up to their fears of strange, scary neighbors; sisters singing songs on the piano and gossiping about the cute new neighbor next-door.

Esther is essentially the protagonist, and many of the film’s narrative developments are seen through her eyes, as a girl well on her way to becoming a young woman. Perhaps for this reason, the harmony of the family’s well-being can only be disrupted by patriarchal forces oblivious to female adolescent tribulations. When an excited Alonzo informs the rest of the family of his promotion in New York City, they are dismayed and resistant to leave their precious home. It’s particularly disastrous for the two oldest daughters, who are on the verge of being proposed to by their respective suitors. The resolution is delayed by seasonal events (a ghoulish, surreal Halloween “episode” involving a maniacal Tootie, and a Christmas ball in which Esther finally goes steady with her crush, John) but the answer comes swiftly to Alonzo by Christmas time, when he witnesses the continued devastation his children suffer from the family’s imminent uprooting. He changes his mind, Esther and Rose’s suitors finally propose, and the World’s Fair opens. Life is good again in magical St. Louis.

Garland soars in the film, but she’s much more than a vehicle for her singing talents. The film’s songs, while iconic to this day, are relatively sparse for a ‘40s musical. Their more unusual characteristic is their employment within the greater narrative context of the film— a precedent that St. Louis set for future studio musicals. Each musical number has a direct emotional and thematic resonance within the film; Garland’s rendition of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” intended to comfort her younger sister (as well as herself) as the two cry over their impending move to New York City, ends up as bittersweet lyricism, encapsulating goals and desires that seemingly will never be fulfilled.

St. Louis is based on Sally Benson’s memoirs of her own family, and the script is tightly structured around a problem that’s only a real crisis for the young and smitten of the Smiths, but that manages to wreak havoc on the entire family. The narrative may ride neatly on waxing and waning events—demarcated by each season with postcard-like photos of the family house, provided by intertitles—but very little conflict actually ensues outside of the looming move. The film feels more like a walk down memory lane than a classical Hollywood story, and Minnelli’s director’s touch gives the impression that the viewer is genuinely looking back on individual childhood reminiscences. The sumptuous tone in an early scene, for example, in which Minnelli’s gliding camera follows a seductive Esther as she obtains John’s assistance in doing the simple yet erotic act of turning off her house lights, is so sensual one can almost smell the perfume she uses to attract him. It’s a testament to Minnelli’s talents, then, that a studio assignment based on a series of cherished memoirs could avoid being redundantly sentimental or perfunctory, and could instead exist in a purely experiential realm that allowed the indelible sensations of memory to seep through the screen.