Dariush Mehrjui’s landmark film The Cow (1969) is largely considered the first film of the Iranian New Wave, the cinema of dissent that emerged at a time when the country’s film industry was still nascent. Insofar as the New Wave directly challenged social norms, it was virtually in direct opposition to the film farsis that made up the backbone of the country’s commercial cinema—formulaic hackneyed productions that poorly imitated Hollywood films while retaining Iranian customs and traditions. The two movements also differed in financing. Through certain cultural funding arms within the government, many New Wave productions were inadvertently and ironically funded by the same government they derided.

The Cow was one of these state-funded projects, though in spite of it winning international awards—a first for Iran—the film was banned by the Shah. Certainly, The Cow provides a bleak commentary on the paranoia and fear that cripple Iranian society—and the unfortunate results of such collective emotions—but it was rather the depiction of Iranians as poor mud-house inhabitants that raised the Shah’s ire, for it ran contrary to his efforts in branding a cosmopolitan Iran to the world. Rather than depicting the macrocosm of Iranian society, however, The Cow is a revelatory and caustic microcosm of societal ills.

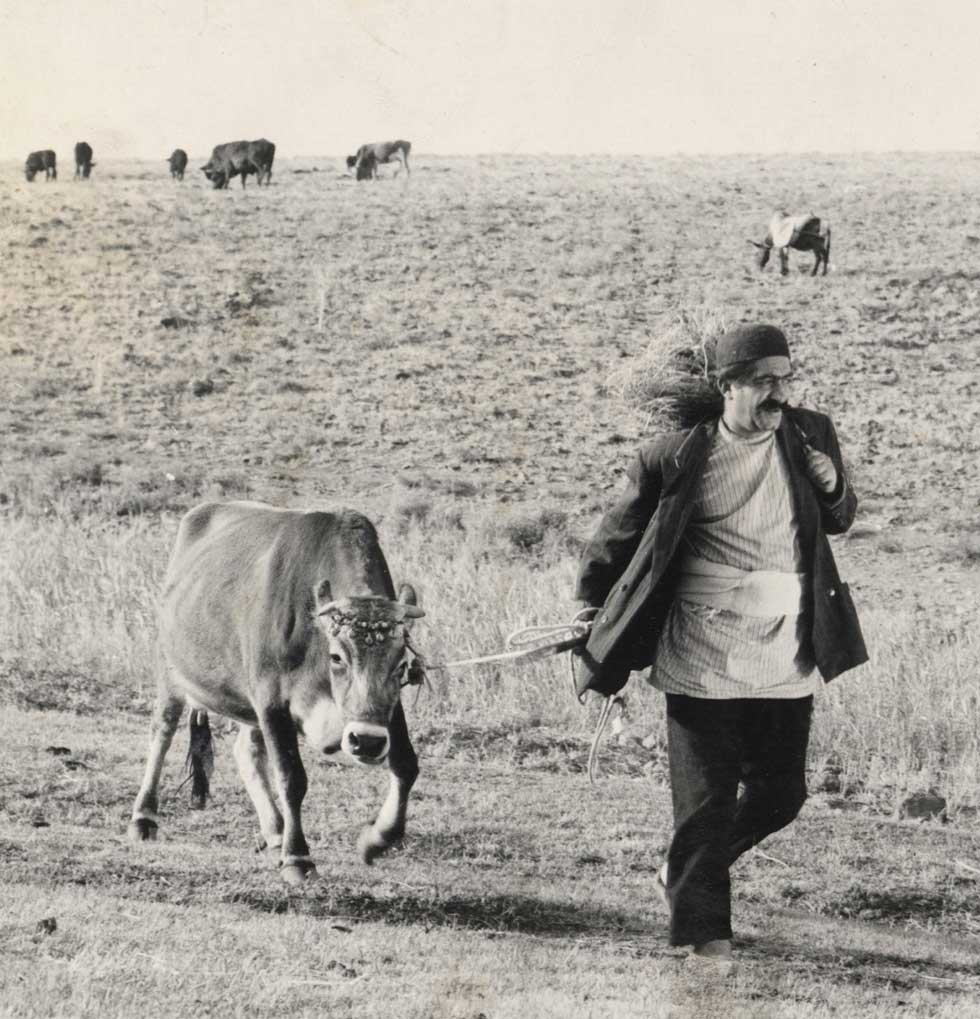

The Cow in question is Masht Hasan’s (Ezzatolah Entezami) beloved bovine, which provides milk for his fellow villagers and is a source of companionship for Hassan. When the cow dies during his absence, the villagers are compelled to lie to Hassan about its mysterious disappearance. Suspecting and feeling betrayed by their mendacity, in addition to a compounding sense of grief over his inability to grieve for her death through the inexplicable lack of its corporeal existence, Hassan begins to slowly transform into the cow. Though the transformation is never treated literally, it is very much in line with the existential crisis of The Metamorphosis. The villagers deny and insolently mock Hassan’s ramblings, but his decline into psychosis in turn leads to the villagers to help him and —ultimately, to their horror—treat him like a mad cow.

Throughout the film the villagers note the sporadic but persistent sightings of the Crystallines, a clandestine group that is deemed threatening to the village. Visually, the Crystallines are only represented as small, dark figures in the distance—inherently unknowable and a deeply symbolic rendering of the village’s fear and paranoia of the unknown. Are these the Savak, the ineluctable influence of Western powers and modernity, the tyrannical reign of traditional Iranian patriarchy or perhaps Persia’s long history of foreign invasion? The Crystallines are never defined as anything more than a potential threat, which allows for a multiplicity of political readings. But fear is not located in the Crystallines alone—it is present in everyday conversations between the villagers, in Hassan’s mind as unconscious states begin to take over, and in the idea of internal enemies (indicative in Hassan’s immediate suspicion of his villagers’ fabrications).

The Cow is regularly—and erroneously—heralded as Iran’s answer to Italian neo-realism. Hassan’s transformation into a cow demonstrates nothing remotely resembling realism, but surrealism, a mode embraced not only by Mehrjui, but by many Persian poets and thinkers of the 1960s who were inspired by contemporary postmodern philosophers. While censors worked to make the film more presentable upon its completion (Mehrjui lied when applying for funds, initially proposing to make a documentary), the board eventually banned it entirely, though an unsubtitled version was smuggled into the Venice International Film Festival in 1971, where it won the film critics award. Forty years later, Iranian films are still being snuck out of the country to screen at film festivals; take, for example, the infamous trek of a USB stick carrying Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not A Film in a cake from Tehran to Cannes. Ironically, The Cow may have been loathed by the Shah, but it was admired by Ayatollah Khomeini.