Caesar Must Die, the 21st film from the infamous Italian brother team Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, won the Golden Bear at Berlinale in 2012. It’s the third top festival award for the brothers, who garnered two Cannes awards in previous decades: the Palme d’Or for Padre Padrone (1977) and the Special Jury Award for La notte di San Lorenzo (1982). Many called the Berlinale jury’s selection “safe” and “conservative;” the film was, after all, competing against Tabu and Barbara. And while Caesar may contain ideas that are at least if not more interesting than Tabu’s black-and-white tale of saudade and Barbara’s subtle GDR morality drama, its execution begins to fall apart at the halfway point.

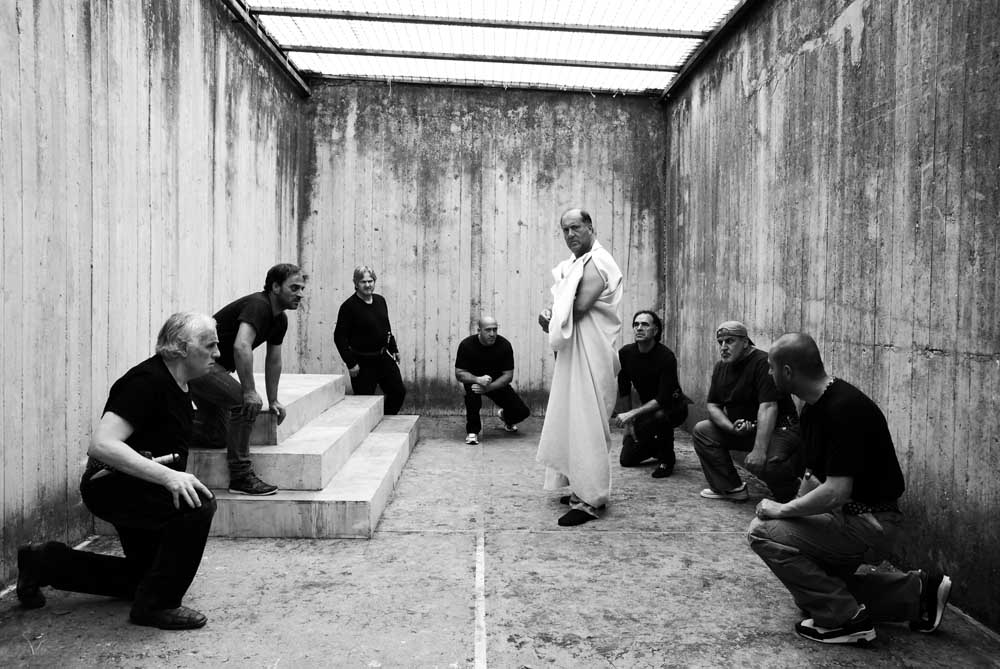

Caesar begins with an intriguing premise: the Taviani brothers film the rehearsal process of William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar at a high-security prison in Italy, but all the scenes appear staged, in individuals’ cells, corridors, yards and meeting halls that look too spotless and lofty to be a real prison. The prison settings are likely genuine, and the camera’s attention away from the smaller details of the surroundings attenuate the significance of the film’s “reality.” The use of a black and white filter, unreserved shadow and bright lighting also help to refine the skeletal dimensions of these spaces whilst fixating on and amping up the theatricality of the play. The same effectiveness of these techniques applies to the subjects, who cannot be accused of “acting” for the camera, as they quite literally are doing just that.

The film’s brilliance surfaces when the prisoners-cum-actors appear to be breaking out of character. Sometimes it’s fairly obvious when this occurs, at other points it takes a few seconds or sentences for context to settle the matter, and on at least a few occasions there is absolutely no certainty. The film is not simply suggesting that the betrayal of Caesar and the play’s political dimensions are relatable for its actors, many of whom were involved in organized crime, but it playfully teases the viewer with the fluidity of real versus scripted language, making the remarkably dramatic play all the more affecting as the reality of prison blends with the increasingly naturalized diegesis of the play. When Bruto (Salvatore Striano) and Cassio (Cosimo Rega) secretly confer at Caesar’s crowning, they look out a barred window that pours out an abundance of natural light and washes out much of the detail in frame. Offscreen we hear shouts and chatter, which one would assume is coming from prisoners in the yard, the diegetic surroundings providing a helpful mock setting for the believability of the scripted scene. Yet when the play director cuts in to provide feedback, the noises stop. These were not the natural sounds of prisoners in recess, but a sound effect that the Tavianis need the viewer to recognize as an orchestrated post-production addition. The film frequently addresses the artificiality of theatre in as many gestures as it does the kind found in cinema. In one scene, the two actors rehearse their lines with other actors and the director present, watching them, as they plan out the scene’s blocking. In the next segment, the camera elegantly dissects the rehearsed scene through parallel editing: Cassio repeats his lines in his cell, which cuts to Bruto repeating his subsequent lines in his own cell. And so on. Once Cassio says, “Trust me, my gentle friend, like I trust you,” the camera pans suddenly to the left to reveal another prisoner playing cards in Rega’s cell, who retorts with “Don’t trust him. Look where trusting got me.” He’d been present the entire time (or had he?), but the camera of course never required to be focused on him. These techniques beautifully explore the advantages of cinema in capturing Shakespeare’s drama and underscores how the film works onlytechnically within the framework of a real theatrical production.

Caesar begins to unthread when its focus moves away from the hybridity between theatre and cinema, and focuses instead on the production of the play itself and the real-life struggles of the prisoners. The film ends with the climactic finale wherein Bruto pleads with a friend to help him kill himself—all of which is filmed at the real show run put on for theatre patrons. By moving away from the liminality proffered by the project to a filmed theatrical production, Caesar undermines its own intelligence. While the subjects’ individual stories are worth capturing on camera, that is worthwhile material for a different film, one that sticks to more tried and true methods of documentary film. It is not necessary to show the subjects being locked back into their cells after the success of their production, neither is the closing scene in which Rega tells the camera “ever since I became acquainted with art, this cell turned into a prison.” Such ideas were already implanted in the first half of the film through elegant implication. This shift—which forces the viewer from contemplating the prisoners as unknowable subjects/characters into exoticized people with “real stories”—is an unfortunate misstep in what is an otherwise excellent film.